|

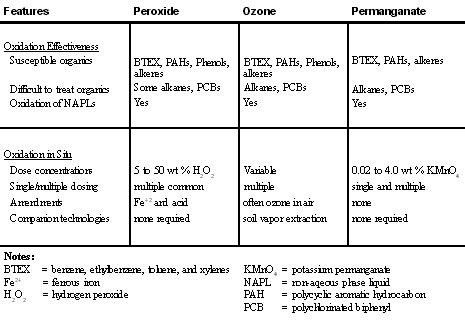

Ground Water Currents, September 2000, Issue No. 37ContentsIn Situ Chemical Oxidation for Remediation of Contaminated Soil and Ground Water Phytoremediation of Ground Water Contaminants Enhanced Biological Reductive Dechlorination at a Dry Cleaning Facility In Situ Chemical Oxidation for Remediation of Contaminated Soil and Ground Waterby Robert L. Siegrist, Colorado School of Mines; Michael A. Urynowicz, ENVIROX, LLC; and Olivia R. West, Oak Ridge National Laboratory Introduction Chemical oxidation/reduction has proven to be an effective in situ remediation technology for ground water contaminated by toxic organic chemicals. The oxidants most commonly employed to date include peroxide, ozone, and permanganate. These oxidants have been able to cause the rapid and complete chemical destruction of many toxic organic chemicals; other organics are amenable to partial degradation as an aid to subsequent bioremediation. In general the oxidants have been capable of achieving high treatment efficiencies (e.g., > 90 percent) for unsaturated aliphatic (e.g., trichloroethylene [TCE]) and aromatic compounds (e.g., benzene), with very fast reaction rates (90 percent destruction in minutes). Field applications have clearly affirmed that matching the oxidant and in situ delivery system to the contaminants of concern (COCs) and the site conditions is the key to successful implementation and achieving performance goals. Oxidants and Reaction Chemistry Peroxide (See Table 1) Oxidation using liquid hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the presence of native or supplemental ferrous iron (Fe+2) produces Fenton’s Reagent which yields free hydroxyl radicals (OH-). These strong, nonspecific oxidants can rapidly degrade a variety of organic compounds. Fenton’s Reagent oxidation is most effective under very acidic pH (e.g., pH 2 to 4) and becomes ineffective under moderate to strongly alkaline conditions. The reactions are extremely rapid and follow second-order kinetics. The simplified stoichiometric reaction for peroxide degradation of TCE is given by equation (a).

Ozone (See Table 1) Ozone gas can oxidize contaminants directly or through the formation of hydroxyl radicals. Like peroxide, ozone reactions are most effective in systems with acidic pH. The oxidation reaction proceeds with extremely fast, pseudo first order kinetics. Due to ozone’s high reactivity and instability, O3 is produced onsite, and it requires closely spaced delivery points (e.g., air sparging wells). In situ decomposition of the ozone can lead to beneficial oxygenation and biostimulation. The simplified stoichiometric reaction of ozone with TCE in water is given by equation (b).

Permanganate (See Table 1) The reaction stoichiometry of permanganate (typically provided as liquid or solid KMnO4, but also available in Na, Ca, or Mg salts) in natural systems is complex. Due to its multiple valence states and mineral forms, Mn can participate in numerous reactions. The reactions proceed at a somewhat slower rate than the previous two reactions, according to second order kinetics. Depending on pH, the reaction can include destruction by direct electron transfer or free radical advanced oxidation—permanganate reactions are effective over a pH range of 3.5 to 12. The stoichiometric reaction for the complete destruction of TCE by KMnO4 is given by (c).

Table 1. Features of Peroxide, Ozone, and

Permanganate Oxidants as Used Design and Implementation The rate and extent of degradation of a target COC are dictated by the properties of the chemical itself and its susceptibility to oxidative degradation as well as the matrix conditions, most notably, pH, temperature, the concentration of oxidant, and the concentration of other oxidant-consuming substances such as natural organic matter and reduced minerals as well as carbonate and other free radical scavengers. Given the relatively indiscriminate and rapid rate of reaction of the oxidants with reduced substances, the method of delivery and distribution throughout a subsurface region is of paramount importance. Oxidant delivery systems often employ vertical or horizontal injection wells and sparge points with forced advection to rapidly move the oxidant into the subsurface. Permanganate is relatively more stable and relatively more persistent in the subsurface; as a result, it can migrate by diffusive processes. Consideration also must be given to the effects of oxidation on the system. All three oxidation reactions can decrease the pH if the system is not buffered effectively. Other potential oxidation-induced effects include: colloid genesis leading to reduced permeability; mobilization of redox-sensitive and exchangeable sorbed metals; possible formation of toxic byproducts; evolution of heat and gas; and biological perturbation. Engineering of in situ chemical oxidation must be done with due attention paid to reaction chemistry and transport processes. It is also critical that close attention be paid to worker training and safe handling of process chemicals as well as proper management of remediation wastes. The design and implementation process should rely on an integrated effort involving screening level characterization tests and reaction transport modeling, combined with treatability studies at the lab and field scale. Conclusions Field tests have proven that in situ chemical oxidation is a viable remediation technology for mass reduction in source areas as well as for plume treatment (See Table 2). The potential benefits of in situ oxidation include the rapid and extensive reactions with various COCs applicable to many bio-recalcitrant organics and subsurface environments. Also, in situ chemical oxidation can be tailored to a site and implemented with relatively simple, readily available equipment. Some potential limitations exist including the requirement for handling large quantities of hazardous oxidizing chemicals due to the oxidant demand of the target organic chemicals and the unproductive oxidant consumption of the formation; some COCs are resistant to oxidation; and there is a potential for process-induced detrimental effects. Further research and development is ongoing to advance the science and engineering of in situ chemical oxidation and to increase its overall cost effectiveness. For more information, contact Dr. Robert L. Siegrist (Colorado School of Mines) at 303-273-3490 or E-mail siegrist@mines.edu. Table 2. Example Applications of In Situ Treatment Using Peroxide, Ozone, and Permanganate

Phytoremediation of Ground Water Contaminantsby Lee A. Newman, College of Forest Resources, University of Washington; and Milton P. Gordon, Department of Biochemistry, University of Washington Phytoremediation relies on natural processes associated with plants to remove contaminants from the environment. This technology can be used to remediate an impressive range of contaminants in a variety of air, water, and soil matrices. Plants have been used in artificial wetland systems to clean surface water and wastewater streams; to remove soluble contaminants such as industrial solvents and gasoline additives that have infiltrated ground-water streams; and to remove airborne pollutants. Plants can enhance the degradation of recalcitrant organic compounds in soils, and they can either accumulate or stabilize heavy metals and radionuclides in the soil. As part of the Superfund Basic Research Program, researchers at the University of Washington have focused on the use of deep-rooted plants such as the hybrid poplar Populous trichocarpa x P. deltoides to treat ground water that has been contaminated with compounds including industrial solvents (e.g., trichloroethylene [TCE] and carbon tetrachloride [CT]); pesticides (e.g., ethylene dibromide [EDB] and dibromochloro propane [DBCP]); and gasoline additives (e.g., methyl-t-butyl ether [MTBE]). To date, the most extensive laboratory and field studies have been done with TCE. Hybrid poplars have proven to be effective in the degradation of TCE. Phytoremediation of Trichloroethylene Early laboratory studies showed that hybrid poplar cells were able to transform TCE to carbon dioxide, trichloroethanol, and di- and trichoroacetic acid. The formation of these metabolites indicates that a complete aerobic degradation pathway exists in the plant cells. Additional work to determine the fate of these compounds in the plants is ongoing. Studies conducted in the laboratory and the greenhouse showed that whole plants were capable of taking up TCE from soil. However, the absolute uptake capacity was unclear, and the amount of metabolites found in the plant tissue was not sufficient to account for the loss of TCE from the systems. Field Studies Application of Technology The University is working on several projects to utilize phytoremediation technology in the field. One site near Medford, OR demonstrated the first application of the “pump-and-irrigate” technology— contaminated water is pumped and applied to the trees via an underground drip irrigation system. In this application, the technology is not limited by the rooting depth of the plants, and the number of sites where phytoremediation can be used is greatly increased. At the Naval Undersea Warfare Center at Keyport Navy Base, WA, two acres of trees are being used to stop the movement of a contaminant plume that is moving toward a sensitive wetland. At this site conventional technologies (pump and treat, and excavation and removal) were considered, but the costs (approximately $10 M) were deemed prohibitive. A state-of-the-art, extensively controlled and monitored phytoremediation system was implemented for $3.5M, resulting in a significant cost savings. In addition, the community support for the phytoremediation project was overwhelmingly favorable, and community visits to the site are common. Conclusions Careful site selection and the application by experienced personnel can advance the use of phytoremediation technology. Additional studies are underway to increase understanding about the fate of various compounds within the plant/rhizosphere system, and to better understand the potential feasibility of this technology under various field conditions. At appropriate sites phytoremediation has the potential to be a cost-effective, low maintenance, and environmentally sound clean up solution for contaminated ground water. For further information contact Dr. Lee Newman at 206-616-2388 or 206-890-1090 or E-mail newmanla@u.washington.edu, or Dr. Milton Gordon at 206-543-1769 or E-mail miltong@u.washington.edu. Enhanced Biological Reductive Dechlorination at a Dry Cleaning Facilityby Judie A. Kean, Florida Department of Environmental Protection; Michael N. Lodato, IT Corporation; and Duane Graves, Ph.D., IT Corporation The dry cleaning industry uses tetrachloroethylene (PCE) as a degreaser and waterless cleanser for clothes. The use of PCE has resulted in the release of this chlorinated solvent at numerous dry cleaning facilities. In the past, many dry cleaning businesses were independently owned with little regulatory oversight regarding the disposal and storage of solvents. As a result, PCE contamination of both soil and ground water at dry cleaner sites is very common. Under the auspices of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, and in accordance with the State’s Dry Cleaning Solvent Cleanup Program, a commercial dry cleaning facility’s soil and ground water was extensively characterized with state-of-the art direct-push diagnostic protocols and statistical data confidence software. The total scope of work was designed to include the evaluation of parameters which give both qualitative and quantitative indications of the occurrence of reductive dechlorination of chlorinated solvents. The combined evidence generated from several different aspects of this evaluation suggested that natural attenuation by the process of reductive dechlorination was occurring, and was significantly affecting the fate of chlorinated compounds in the aquifer. Measurable levels of cis-1,2-DCE (dichloroethylene) and vinyl chloride supported the conclusion that reductive dechlorination of PCE and TCE (trichloroethylene) affected the chemical composition of a dissolved contaminant ground-water plume. Upon evaluation of all assessment data, it was determined that an area of approximately 14,600 square feet of contaminated ground water was situated within the 1 mg/L isopleth for PCE; and in some monitoring wells contaminant concentrations approached 9 mg/L. HRC Application and Monitoring Program Approximately 6,800 pounds of Hydrogen Release Compound (HRC) were injected into the area described via 144 direct-push points spaced 10 feet apart on centers within an 80-ft by 180-ft grid. HRC is a proprietary, environmentally safe, food quality, polylactate ester made by Regenesis Bioremediation Products, Inc. It is specially formulated for slow release of lactic acid upon hydration. HRC is applied to the subsurface via push-point injection or within dedicated wells. HRC is then left in place where it passively works to stimulate rapid contaminant degradation. At the Florida site, each point received 2.45 gallons of HRC between a depth of 5 to 30 feet below the surface in the upper surficial aquifer. The effects of HRC on ground-water geochemistry and chlorinated solvent concentrations were determined by periodically sampling and analyzing ground water from seven monitoring wells. Analysis included chlorinated solvents, dissolved oxygen, oxidation-reduction potential, pH, conductivity, temperature, ferrous iron, nitrate and nitrite, sulfate, methane, ethane, ethene, manganese, and phosphorus. Ground-water samples were collected for six months following the HRC application to monitor progress of the treatment. Results The application of HRC resulted in an observable change in the concentration of chlorinated solvents. An area approximately 240 by 180 feet was affected by the HRC application. The mass of PCE and its dechlorination products before HRC application and at various time points after the application is shown in Table 3. Table 3. Mass of Chlorinated Hydrocarbons at Various Times After HRC

The PCE mass increased from the initial mass to the mass estimated after 43 days. This change was presumably due to physical desorption related to the injection activity. Overall the PCE mass was reduced by 96% after 152 days of treatment. The dramatic reduction in PCE mass and the less dramatic reduction of the mass of the lesser chlorinated ethenes suggests that the PCE was being dechlorinated to TCE, DCE, and vinyl chloride. HRC-stimulated, biologically mediated, reductive dechlorination of PCE was confirmed by changes in ground-water geochemistry that are typically catalyzed by biological activity. The overall results from HRC application and continued monitoring indicated that HRC appears to be an effective alternative for remediating PCE, TCE, cis-1,2-DCE, and vinyl chloride in ground water. The cost for this large-scale demonstration was favorable and should encourage the application of the technology at appropriate sites. The overall cost of this project was $127,000. HRC product cost was $27,197. Additional project costs included the preparation of a detailed work plan, sampling and analysis plan, health and safety plan, preparation of an underground injection permit, hiring of a Geoprobe subcontractor, labor, monthly reports and meetings, contractor oversight, and field and laboratory analyses. This project represents the successful collaboration of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Regenesis Bioremediation Products, and IT Corporation, the state cleanup contractor. For further information about this specific project, contact Judie Kean (Florida Department of Environmental Protection) at 850-488-0190. For information about the HRC product, contact Steve Koenigsberg (Regenesis Bioremediation Products, Inc.) at 949-366-8000, ext. 106.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||