Characterization, Cleanup, and Revitalization of Mining Sites

Case Studies

EPA; other government agencies; state, local, and tribal governments; as well as private entities have successfully remediated and restored numerous current, former, and abandoned mining areas throughout the United States. This page presents some of these successfully restored sites as well as sites still in progress. More detailed information about these sites can be found by visiting the links under each case study.

For a more comprehensive list of abandoned mine lands and abandoned mine restoration projects, visit the EPA Abandoned Mine Lands program website. See also, the case studies compiled by the Interstate Technology Regulatory Council's (ITRC) Mining Waste Team.

↩Hard Rock Mines

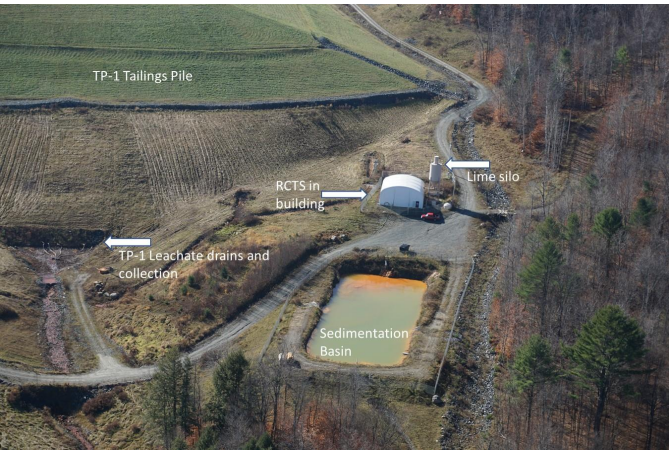

Historical mining operations at the Elizabeth Mine contaminated local water bodies with mining wastes and mine drainage. An active treatment approach was selected for the leachate emanating from the base of a tailings pile due to the mine's location, available land area, and the high levels of iron. The Rotating Cylinder Treatment System™ (RCTS™) followed by a sedimentation basin was constructed. The RCTS is a form of lime (calcium hydroxide) precipitation treatment. Contaminated water is mixed with lime slurry in shallow troughs while rotating perforated cylinders aerate and agitate it. Precipitated metal hydroxides and oxides coat the lime particles which are removed in the sedimentation basin. Over eight years of seasonal operation from 2009-2017, the remedy effectively lowered the maximum annual total iron concentration treated from 1,700 mg/l to less than 1mg/l.

From 1947 to 1965, kyanite was open-pit mined atop Henry's Knob. Ore-grade rock was ground up and processed by flotation to liberate kyanite from the ore. The leftover ground-up waste rock and spoils were dewatered and left in piles onsite. Today, the responsible party is working with state and federal agencies to take an adaptive management approach to mitigate ongoing erosion of the mine tailings and minimize the potential for further impacts to groundwater and nearby streams from acid mine drainage.

This adaptive management approach involves stepwise implementation of media-specific remedies that are evaluated for effectiveness. The first step is to revegetate the barren tailings areas to reduce their erosion and the infiltration of water. The goal is to decrease the acid mine drainage impacting groundwater and nearby streams. Studies were conducted to create a soil profile with a sufficient organic content and pH to support the growth of native vegetation and pollinators. The local cooperative extension, EPA and SC Department of Health and Environmental Conservation helped the responsible party add a pollinator seed mix to the original pilot study mix that would both establish native plants and support pollinators for all plantings. Native vegetation and pollinator habitat are now well established on the tailings areas, and all of the tailing areas will be vegetated by the mid-2018. Several lessons have been learned thus far from the adaptive management process: consider revitalization options early in the cleanup process; use local knowledge and materials, when possible; consider new cleanup ideas as well as traditional ones; and purchase materials locally. Monitoring is ongoing to evaluate the effectiveness and other benefits of revegetation. Based on this evaluation, the need for a groundwater remedy will be assessed.

Contamination from nearly 100 years of copper smelter operations affected the health and quality of the environment at the Ancaconda Smelter Site. Estimates indicate that more than a billion gallons of groundwater were contaminated and thousands of acres of soil were affected by fluvially transported mine wastes and smelter emissions. The massive 300-square-mile site area and variable, rugged terrain provided major remedial design challenges. The innovative site evaluation and assessment techniques, paired with effective remedial processes such as tilling and adding soil amendments, have helped restore these vital grasslands and ranch areas. The uplands remediation and ecological revitalization efforts have served to provide key lessons and replicable assessment techniques for other sites with area-wide contamination.

The Silver Mountain Mine site is an abandoned silver and gold mine that operated from 1928 to the 1960s. In the early 1980s, cyanide was used to extract metals from mine tailings. By 1983, the site was abandoned, and the mine tailings and holding basin, which contained cyanide-contaminated water, were left behind. A leachate collection trench associated with the ore extraction was contaminated with cyanide and arsenic.

This site was added to the NPL in 1986. Sodium hypochlorite was used to neutralize the cyanide in the pond and in the mine tailings. The contaminated water in the leachate collection trench was then removed from the site. The trench was covered with a liner. In the 1990s, approximately 7,000 cubic yards of mine tailings were consolidated and capped, the mine entrance was closed, and the site was revegetated and fenced. Deed restrictions were implemented to protect the cap. The site cleanup was designed to require very little maintenance. The site was deleted from the NPL in 1997. As of 2008, the cap is in excellent condition and the fence remains in place. The Washington Department of Ecology will continue to perform annual inspections and maintenance of the cap.

Yak Tunnel (one of two tunnels that drain the historic mining district) prior to construction of the Yak Water Treatment Plant (Source: EPA)

The California Gulch Superfund site consists of about 18 square miles of land where mining, mineral processing and smelting activities produced gold, silver, lead and zinc for more than 130 years. Wastes generated during the mining and ore-processing activities contained metals such as arsenic and lead at levels that posed a threat to human health and the environment. These wastes remained on the land surface and migrated through the environment by washing into streams and leaching contaminants into surface water and groundwater. The site was added to the NPL in 1983. To facilitate cleanup, it was divided into 12 operable units, each with a specific cleanup activity. EPA and the potentially responsible parties conducted removal and remedial activities to consolidate, contain, and control more than 350,000 cubic yards of contaminated soils, sediments and mine-processing wastes. Cleanups by the potentially responsible parties have involved drainage controls to prevent acid mine runoff, consolidation and capping of mine piles, and slag reuse. By 2011, several of the operable units at the site were deleted from the NPL. Response actions are complete in most of the operable units, and institutional controls to protect the remedy and prevent the release of contaminants are either in place or under development.

For more information on California Gulch

Making a Difference in Communities: California Gulch Superfund Site, Leadville, Colorado (Video)

The Copper Basin Mining District has been heavily scarred by mining activities that continued from the mid-1800s until the late 1900s. Mining and processing activities centered on copper and sulfur, and produced solid wastes and byproduct materials that remain on site, including sulfide-rich ore, sulfide-bearing waste rock, tailings, granular and pot slag, iron calcine, magnetite, iron concentrate, wastewater treatment sludge, and demolition debris. In addition, mining and related activities resulted in contamination by metals and polychlorinated biphenyls, deforestation, and severe erosion.

Several government agencies and private parties have taken steps to stabilize and partially revegetate the area, including its numerous watersheds. The site is being investigated and cleaned up through a collaborative effort between the EPA, the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, and OXY Oil and Gas USA. A wastewater treatment plant was refurbished on the Davis Mill Creek watershed to treat acid and metal-laden waters of the creek, underground mine waters, and contaminated stormwater. The plant has removed over 5 million pounds of iron, zinc, manganese, copper, lead, and cadmium, and neutralized over 13 million pounds of acid. The Davis Mill Creek watershed also received diversion systems and upgrades and modifications to existing dams. The North Potato Creek received a lime treatment plant that removed 90 percent of metals of ecological concern and raised the pH of the discharge from 3.3 to 7.0. One of the goals for this watershed is to reestablish its biological integrity. This process is currently in progress.

From 1916 and to the 1980s, lead and zinc were mined and smelted at the Bunker Hill site. The West Page Swamp was used as a tailings repository for a mill that processed the lead and zinc ore. The soil in this area contained highly contaminated lead and zinc tailings, materials so toxic that the swamp showed no evidence of ecosystem function. Following removal of tailings to a depth of 0.7 meters, a cap consisting of biosolids (including compost, wood ash and wood waste) was constructed over over the soil. This cap was sufficient to reduce both accessibility and bioavailability of the underlying tailings and restore ecosystem function, characteristic of a naturally occurring wetland to the site. The wetland is now fully functioning and a wildlife habitat.

Coal Mines

Site before Stream Restoration - Yankee-Vukonich Coal Reclamation Project, Colfax County, New Mexico (Source: New Mexico Mining and Minerals Division)

Site after Stream Restoration - Yankee-Vukonich Coal Reclamation Project, Colfax County, New Mexico (Source: New Mexico Mining and Minerals Division)

Mining from the 1800s until the 1970s produced substantial amounts of coal waste at the Yankee-Vukonich Coal Reclamation Project site. The majority of the waste was found dumped down steep slopes and near streams, where it was contaminating both ephemeral and perennial waterways. Partially collapsed mine entrances also were a major issue.

The reclamation project for the 2.9-acre site was completed in 2005. The goal of the project was to establish vegetation on coal mass piles to reduce erosion and siltation of downstream waterways, and to restore the meanders of the stream that had been straightened by sediment deposition during the active mining period. Revitalization activities included mixing coal waste with native soil while adding lime, gypsum, wood waste, and compost to support native vegetation; reseeding at designated areas and areas disturbed by construction; restoring stream meanders through excavation, filling, and engineered structures; and others. The project has successfully restored vegetation at the site so that it blends in with undisturbed areas. In addition, streams have been reshaped to a natural state and historic buildings from the mining era have been preserved.

For more information on Yankee-Vukonich Coal Reclamation Project

Maude Mine Reclamation Project, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania (Source: Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation)

The Fishing Run Restoration and Maude Mine Reclamation Project site was mined from the 1800s through the early 1900s. Large-scale underground mining operations began toward the end of the 19th century to keep up with energy demand generated by the growing steel industry in Pittsburgh. The site included an open portal, a partially sealed mine opening, 1,500 feet of hazardous highwall, and numerous dilapidated coal-facility structures. The open mine portal captured and diverted all of the flow from the upper portion of the Fishing Run stream. The water captured by the portal flowed through an abandoned mine and then discharged as acid mine drainage into a major stream.

Specific reclamation and revitalization activities included the demolition, removal, and disposal of the abandoned coal preparation structures; elimination of the highwall areas through excavations and fills; and sealing of the open mine portal and a partially sealed mine opening. In addition, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection's Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation restored Fishing Run to a natural streambed, which is now lined with over 4,000 trees for stream-bank restoration and establishment of a riparian buffer zone.

For more information on Fishing Run Restoration and Maude Mine Reclamation Project

Geotextile material and trees and shrubs installed onsite (Source: New Mexico Mining and Minerals Division)

The Swastika Mine and Dutchman Canyon Reclamation Project received a 2012 Excellence in Reclamation Award from the New Mexico Energy, Minerals, and Natural Resources Department's Mining and Minerals Division. The project is located about 4.5 miles northwest of Raton, New Mexico.

The Swastika Mine was established in 1919 and was mined for coal through 1954. Mine waste material was dumped directly into the Dillon Canyon stream, which was artificially straightened to provide room for railroad and loadout facilities. The reclamation project involved work to safeguard hazardous mine features at the abandoned mine and to restore meanders of the stream channel. Mine waste piles were moved away from the main stream channel and reshaped into stable landforms that mimic natural hill slope forms using a technique called geomorphic reclamation.

The Dutchman Mine is a much smaller mine in a side canyon nearby. Operations began in 1898 and closed in 1906 following a methane explosion that killed ten men at the site. Here, alkaline drainage from collapsed mine adits were treated using a pond and constructed wetland. Extensive wetland improvements were made to the reconstructed Dillon Canyon channel and to an existing evaporation pond that intercepts mine seepage at Dutchman Canyon.

This is the first large geomorphic reclamation project within the New Mexico Abandoned Mine Land Program. About 200,000 cubic yards of mine waste and 190,000 cubic yards of clean fill were moved. Challenges included a high-voltage power line, numerous archaeological features, construction in a narrow canyon, and a running stream.

For more information on The Swastika Mine and Dutchman Canyon Reclamation Project

Hazardous highwall and highly acidic water impoundment at Dents Run Watershed site PA 3898 prior to reclamation. (Source: Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation)

Aerial view of site PA 3898 after reclamation. (Source: Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Abandoned Mine Reclamation)

The Dents Run AML/AMD Ecosystem Restoration Project is a $14.2 million mine restoration project conducted in the Dents Run watershed in Elk County, Pennsylvania by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP) and partners.

Over 50 years of excavation, underground 'room and pillar' mining, and strip mining for coal in the 25 square mile watershed had severely degraded the landscape and water quality of surrounding streams. Highwalls, water impoundments, mine openings, and hundreds of acres of acid mine spoil required cleanup and revitalization. Because passive or active treatment alone would be costly and technically difficult to achieve, a combined reclamation and treatment/abatement effort was undertaken. Between 2002 and 2012, PA DEP closed or remediated 23 mine openings and regraded ten dangerously steep highwalls that totaled 30,850 feet. More than half a million tons of limestone were mined at the site and used to neutralize the thousands of gallons of acidic mine water that was flowing through the site from 14 different discharge points. More than 5,000 cubic yards of waste coal were removed from the site and used as fuel at a coal-fired power plant, providing electricity to homes and businesses.

The reclamation project restored and re-vegetated 320 acres of abandoned mine lands that will now serve as habitat for wildlife, including the state's wild elk herd, which roam the adjacent Elk State Forest and game lands. Almost five miles of the lower Dents Run stream also were restored by neutralizing acid mine water. The stream can now support aquatic life for the first time in more than a century.

Uranium Mines

The Navajo Nation is situated on a geologic formation rich in radioactive ores including uranium. Beginning in the 1940s, widespread mining and milling of uranium ore for national defense and energy purposes on the Navajo Nation led to a legacy of abandoned uranium mines. Some Navajo residents may have elevated health risks due to the dispersion of radiation and heavy-metal contamination in soil and water.

EPA maintains a strong partnership with the Navajo Nation. Since 1994, the Superfund program has provided technical assistance and funding to assess potentially contaminated abandoned uranium mine sites and develop a response. In August 2007, the Superfund program compiled a Comprehensive Database and Atlas with the most complete assessment to date of all known uranium mines on the Navajo Nation. Working with the Navajo Nation, EPA also used its Superfund authority to clean up four residential yards and one home next to the highest priority abandoned uranium mine, Northeast Church Rock Mine, at a cost of more than $2 million.

EPA maintains a strong partnership with the Navajo Nation. Since 1994, the Superfund program has provided technical assistance and funding to assess potentially contaminated abandoned uranium mine sites and develop a response. In August 2007, the Superfund program compiled a Comprehensive Database and Atlas with the most complete assessment to date of all known uranium mines on the Navajo Nation. Working with the Navajo Nation, EPA also used its Superfund authority to clean up four residential yards and one home next to the highest priority abandoned uranium mine, Northeast Church Rock Mine, at a cost of more than $2 million.

In 2008, EPA, in partnership with the Department of Energy, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Indian Health Service and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, finalized a five-year plan for cleaning up the abandoned uranium mining on the Navajo Nation. Under the Five-Year Plan, U.S. EPA works with the Navajo Nation EPA to conduct a tiered assessment of abandoned mines, identify mines for more detailed assessments, and determine appropriate courses of action for the highest-priority mines. By the spring of 2010, EPA completed 192 on-site screen evaluations of abandoned uranium mine sites in the Eastern and Northern abandoned uranium mine regions and completed more detailed assessments at four additional mines. In 2011, EPA expected to conduct screening-level review and site visits of an additional 134 abandoned uranium mine sites in the Northern and Western abandoned uranium mine regions. EPA also completed removal assessments for the Skyline Mine and the Northeast Church Rock "Quivira" Mine.

In September 2008, EPA Region 8 certified the completion of the 20-year, $120-million cleanup of the Uravan Mill Superfund site in Colorado. The former uranium and vanadium mine and processing site is located along the San Miguel River in western Montrose County. The 680-acre site is contaminated with radioactive residues, metals and other inorganic materials.

During the cleanup, more than 13 million cubic yards of mill tailings, evaporation pond precipitates, water treatment sludge, contaminated soil, and debris from more than 50 major mill structures were collected and disposed in four on-site repositories. More than 380 million gallons of contaminated liquid collected from seepage containment and groundwater extraction systems were treated at the mill site. The site and surrounding area will be used in the future for recreation and as a wildlife habitat. One portion of the site will be transferred to DOE for long-term management, while another will be used as a campground and visitor center, complete with a museum dedicated to uranium mining and milling in Western Colorado.